Jesse Rifkin is a writer, historian and tour guide in New York City. His latest book, This Must Be The Place: Music, Community and Vanished Spaces in New York City, examines the fascinating history of how “real estate, gentrification, community and the highs and lows of New York City itself shaped the city’s music scenes from folk to house music.” This month, the SoHo Broadway Initiative is diving into the neighborhood’s music history, specifically the significance of joint live-work spaces as integral sites for the rise of “minimalism” and “loft jazz.”

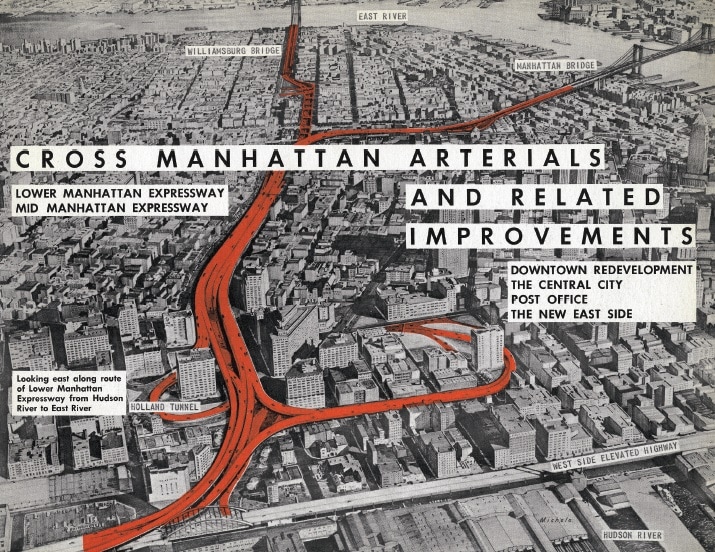

In the 1960s, SoHo’s cast-iron industrial lofts were abandoned as manufacturing jobs moved out. At the same time, Robert Moses campaigned for the construction of the Lower Manhattan Expressway (LOMEX) which would have displaced residents of the Lower East Side, SoHo and Little Italy.

Source: Gotham Center for New York City History

Jane Jacobs and other community members organized a successful resistance to the LOMEX proposal, and with the neighborhood’s future in flux, artists started occupying the upper floors of abandoned industrial lofts. These wide-open spaces with few neighbors were conducive to visual and musical artists alike. George Maciunas is referred to as the “Father of SoHo” for his contributions to the movement coalescing around joint live-work spaces for artists and their families. With grants from National Endowment of the Arts, Maciunas converted industrial lofts to live-work spaces like the one pictured below.

Source: Artsy

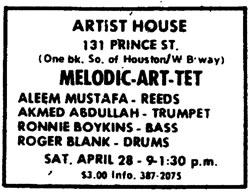

Live jazz music grew out of Harlem house parties in the 1920s. It was common for musicians to attend “jam sessions” at residential apartments, and by the 1950s traditional music venues in the West Village and SoHo regularly welcomed jazz performances. In 1961, world-renowned jazz musician Ornette Coleman moved into 131 Prince Street in SoHo where he converted the first floor of the building into a rehearsal and music venue (later named “Artist House.”)

Source: Point of Departure

Coleman’s 1970 album Friends and Neighbors was recorded at 131 Prince Street and exemplifies the qualities of “loft jazz”: a mix of modern, avant-garde, and improvised music heavily influenced by the traditions of jazz, classical, and Asian music. La Monte Young, Ornette Coleman, Yoko Ono, and John Cale are important contributors to the rise of Downtown’s loft jazz scene.

Source: Point of Departure

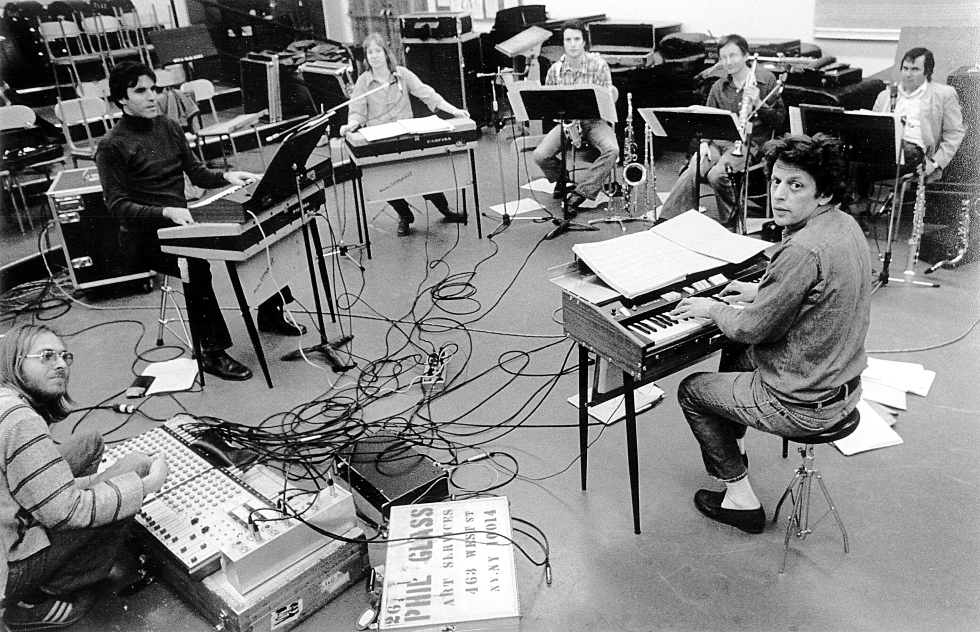

Classical composers Steve Reich and Philip Glass are credited for the rise of “minimalism”—the genre Rifkin describes as a modern extension of classical music “reduced to simple shapes and textures, leaning heavily on repetitive, cyclical phrases, rhythmic pulses, and/or drones.” Since classical music venues were not interested in minimalist music at the time, artists created a space for their music in SoHo’s industrial lofts where formal and informal performances and rehearsals were held. Below is a photo of Steve Reich and other musicians rehearsing at Reich’s loft.

Source: Richard (Dickie) Landry

The physical environment heavily influenced the musical output; musicians could arrange themselves in circles and play to an engaged audience. Regular performances were held at Donald Judd’s loft at 101 Spring Street, suggesting shared support between minimalist artists of all kinds. In the 1970s, Glass moved into the upper floor of 10 Bleecker Street where the Philip Glass Ensemble worked on the seminal composition, Music in Twelve Parts.

Source: Philip Glass Ensemble

SoHo continued to play a role in the evolution of other NYC music scenes in the following years. In the mid 1970s, The Gallery at 172 Mercer Street, the Flamingo at 599 Broadway, and the Loft at 99 Prince Street served as hotbed for disco. Proto-punk and art-rock bands like the Modern Lovers and Talking Heads performed at The Kitchen at 59 Wooster Street. In 1981, members of emerging experimental rock band Sonic Youth organized Noise Fest at White Columns, a gallery at 325 Spring Street featuring several no wave bands over the course of a week.

While the epicenter of underground music communities migrated elsewhere in Manhattan in the decades that followed, and ultimately to Brooklyn and even Queens, the lofts of SoHo served as fertile ground for the development of important avant garde scenes in their prime.

Want to read more about the history of NYC music spaces? You can purchase Rifkin’s book here or visit your local bookstore!