As May begins with International Workers’ Day, this month we are looking back on the struggles, fights and gains of the labor movement locally, as illustrated by the history of 427-429 Broadway.

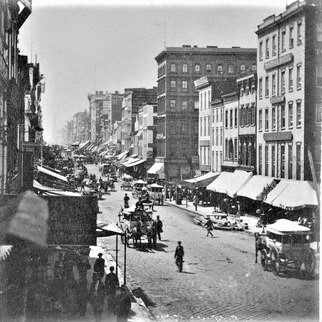

427-429 Broadway was originally home to one of the district’s major hotels: the City Hotel, which was later renamed the Tontine Hotel after the Civil War. It was in a prime location that was a short walking distance from three major train stations: the Harlem, New Haven and Hudson River Depots. Around the mid-1800s, the neighborhood along Broadway and Howard Street was increasingly becoming more commercial in nature.

By 1870, the hotel was demolished and to be converted into a modern loft and retail building. For this project, architect Thomas R. Jackson enlisted a relatively new innovation at the time: a cast-iron facade. It involved installing pre-fabricated cast iron components to masonry fronts of buildings, imitating carved stone. Additionally, it made the facades fireproof. Jackson dressed the facade with intricate French Rennaisance decorations in cast-iron. As a major advantage of cast-iron is the speed of construction it enables, the building was completed within a mere six months.

The building was home to many merchants, from those that specialized in fur to dry goods sellers. John M. Davies & Co. moved into the building in 1876. In a blog post a source describes the company as “the leading house and originator in men’s furnishing goods.” Unfortunately, this company was the site of much tension with its workforce. Conflict initiated with the hiring of a new superintendant named Schautz with an annual pay that was $3000 over his predecessor, Straub. Straub had been fired by the company for being pro-union.

The workers stated that they were fond of Superintendent Straub, and attemped to continue their work as they had before following his replacement by Schautz. Workers believed the the change in management would not impact them greatly. When Schautz came in, his plan was to “thoroughly reorganize the working system of the factory by following a policy of the most rigid economy.” He began with a 10% reduction in workers’ wages. However, the staff noticed that many of Schautz’s friends that joined the company were brought in with much higher wages. Long-time employees were laid off and many of the new men brought in made more than those that were removed.

A major breaking point was in 1887, when Schautz told female workers that he was to slash their wages by $3-$4 per week (approximately $111 in today’s currency). The workers fought back claiming that “no respectable girl can board and clothe herself on that amount.” Schautz appeared to agree in order to appease the workers.

However, the workers were deceived when a few days later came another cut which averaged 50 percent over all classes of work. Schautz declined to meet or speak with the women, eventually leading to the entire female workforce walking out. A New York Times article from July 1887 states that the entire factory was essentially shut at the time, with very few workers and no female employees inside the factory. Schautz told the Times that he was certain that the women would submit to his terms in a few days. The women counteracted by suggesting that all they wanted was “a fair show”, and that if the company was so short on finances, Schautz should instead “knock something off of his own salary.”

Ultimately, the strike was resolved, however the end of the firm was near. The company shut down three years later in 1890. Today, even after a century and a half, the building still stands intact with its cast-iron facade and as a forgotten footnote in the history of the labor movement.