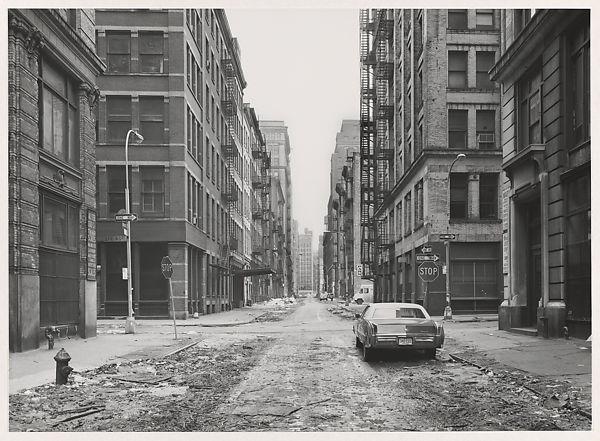

To speak of the historic character of SoHo usually brings to mind a few specific characteristics of the neighborhood: cast-iron architecture, artists, and lofts. As the story goes, in the mid-20th century the lofts in SoHo’s renowned cast-iron buildings were empty and abandoned as a result of urban renewal programs to clear New York City of its so-called “slum” districts. In the 1970s, artists moved into these lofts and were able to save the buildings and save SoHo by transforming the area into NYC’s artist residential district. For many, this is the foundational history of the neighborhood, yet in reality this narrative is closer to mythology than history.

In 1982, urban sociologist Sharon Zukin began to take notice of the phenomenon of residential loft conversion, seeing that Lower Manhattan’s once-thriving manufacturing zones were becoming live-work space for creative workers, domiciles for the middle-class, and NYC’s trendiest new living situation for the business professional. She released this study in the form of a book, Loft Living: Culture and Capital in Urban Change; in her book, Zukin outlines the economic and political changes that influenced the abandonment of manufacturing in Manhattan and impacted the culture surrounding residential loft conversion.

Zukin lays out the popular mythology of residential loft conversion, which paints areas like SoHo as some imaginary wilderness that creatives like artists helped settle, leading to interest from middle-class buyers:

“The presence or supply of underused loft buildings supposedly inspired an inventive adaptation. Demand for lofts emerged among worthy, though unworldly, artists and performers. They settled bravely in the urban tundras and carved neighborhoods out of the wilderness. Just when they had succeeded in taming their cast-iron environment, a band of new arrivals—who were interested in domesticating an industrial aesthetic—moved into the territory. Recognizing neither claims nor conventions, the wave of loft tenants bid up property values, started boutiques, and crowded out the original settlers with their purely residential ethos. They outlawed mixed use. They had no sense of mission.”

Yet, Zukin refutes this narrative by claiming “…the market in living lofts appears as the newest battlefield in the struggle for control over the city. While loft tenants are the obvious pawn in the struggle…” To start, neighborhoods like SoHo were not “urban tundras and wilderness” but themselves had been vibrant manufacturing neighborhoods; though the city lost manufacturing jobs in the ’70s due to the fiscal crisis and a general recession, a shifting economic landscape is not entirely to blame. Some manufacturers claim that the loss of manufacturing in SoHo and other loft neighborhoods in the city was also the result of landlords refusing to rent to manufacturers, instead holding out in order to take advantage of higher rents they could potentially receive through a residential conversion:

“…by the middle of the 1970s, manufacturing tenants started to complain vociferously—to [the City Planning Commission], to the mayor, to anyone who would hear them—that their landlords deliberately created and maintained vacancies in order to facilitate residential conversion. So the sequence of deindustrialization, on the one hand, and vacancies, arrears, and foreclosures, on the other hand, may have been somewhat skewed by the conversion process itself.”

The loss of manufacturing is SoHo wasn’t as passive of a phenomenon as the mythology lets on, nor was the residential conversion. The residential turn of the loft neighborhoods was already in the works before SoHo became SoHo—though while the actual form of the neighborhood as an artist enclave was unplanned, the groundwork was laid in order to facilitate transforming the urban core of Manhattan away from its working-class identity since after WWII:

“In many ways the emergence of loft living in New York was as unplanned a development as the city government and the real estate industry claim it was. But it was hardly ‘spontaneous.’ The preconditions for converting manufacturing lofts to other uses had been established as far back as 1945. They were set, in the long run, by the divestment of financial institutions from an infrastructure that served light industry and, in the short run, by economic and political factors that worsened the already shaky conditions of competitive capital—the small businesses and small manufacturers that were ensconced in loft buildings. In terms of the cultural values that made loft living worthwhile, the real estate market in living lofts was set up to sell the social changes of the 1960’s to middle-class consumers in the seventies and eighties. The creation of constituencies for historic preservation and the arts carried over a fascination with old buildings and artists’ studios into a collective appropriation of these spaces for modern residential and commercial use. In the grand scheme of things, loft living gave the coup de grâce to the old manufacturing base of cities like New York and brought on the final stage of their transformation into service sector capitals. The form itself sets up a matrix of accumulation and consumption, cultural expression and social control, that changes the nature of urban space. As a real estate market, too, loft living acts as a vehicle for deindustrializing local capital and thus, paradoxically, for making the specific historic legacy of the built environment conform to world market trends.”

For better or worse it is clear that SoHo’s proliferation of living lofts was not entirely a countercultural phenomenon but had its groundwork orchestrated since the mid-20th century. The information presented here only touches on some of the contradictions and realities that have helped shaped SoHo’s partial residential conversion, for a more in-depth analysis we encourage you to read Zukin’s Loft Living. That being said, the effects of the artists on the neighborhood shouldn’t be downplayed; the SoHo artist tenants have always been a vocal fixture of the neighborhood fighting for their live-work lofts, advocating for the Loft Law, and helping to establish the neighborhood as an arts district. To learn more about the impact of the arts on SoHo, check out this podcast done with Aaron Shkuda, the author of The Lofts of Soho: Gentrification, Art, and Industry in New York.

Note: This post was contributed by SoHo Broadway Initiative Community Engagement and Planning Intern Matthew Morowitz, who departs us this month. The Initiative thanks Matthew for all of his work and wishes him the best wherever he may go!